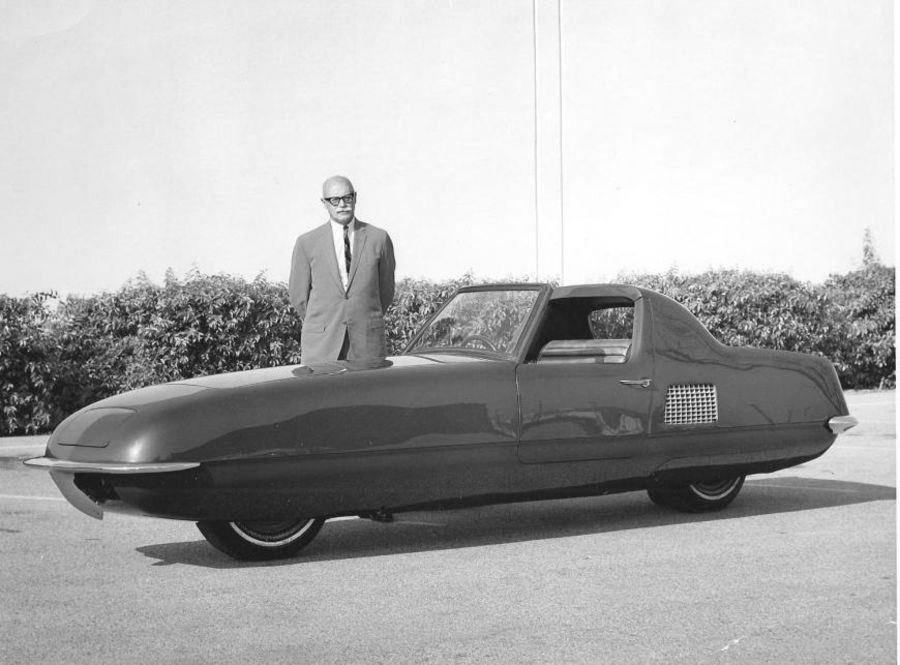

Alex Tremulis was a man with a lively mind. The chief designer of Auburn, Cord and Duesenberg, the architect of the Tucker and the longtime head of Ford’s advanced design studios, Tremulis was fascinated by the future. In his later years, active as ever, he became captivated by the idea of gyro-stabilized vehicles: railcars, motorcycles and automobiles (the latter expressed in the Ford Gyron concept car).

One of the products of that thinking, known as the Gyro-X, has only recently emerged from obscurity in the sympathetic hands of the Lane Motor Museum in Nashville, where founder Jeff Lane aims to have it restored and operational by the centenary of Tremulis’s birth in 2014.

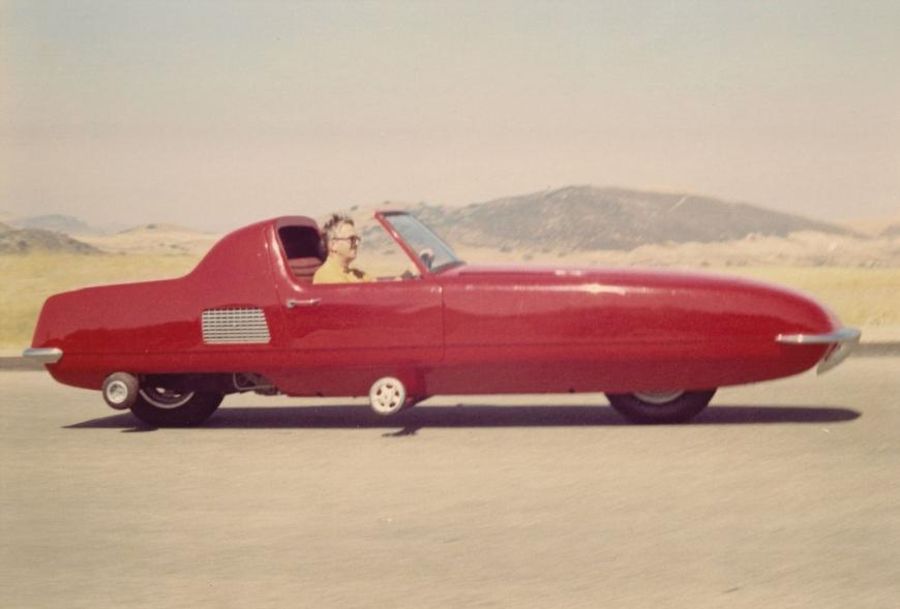

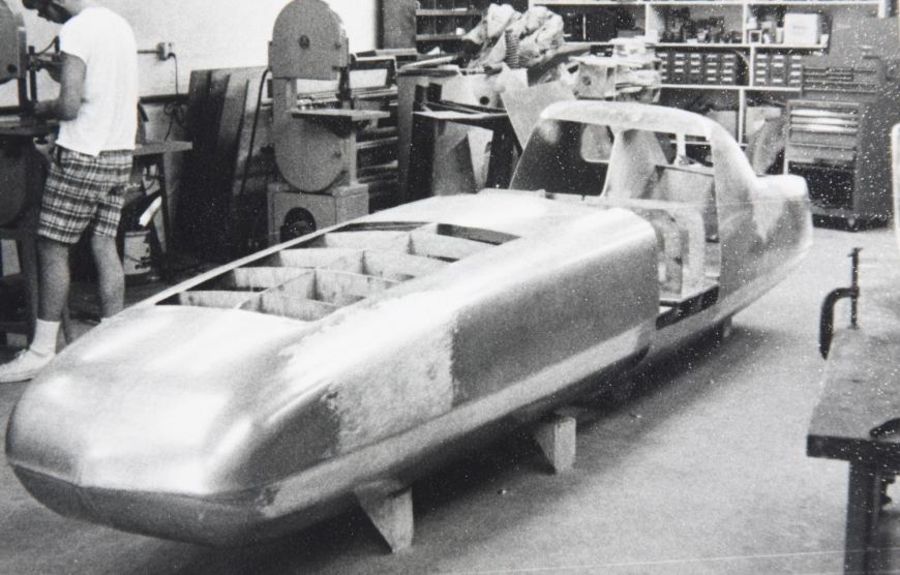

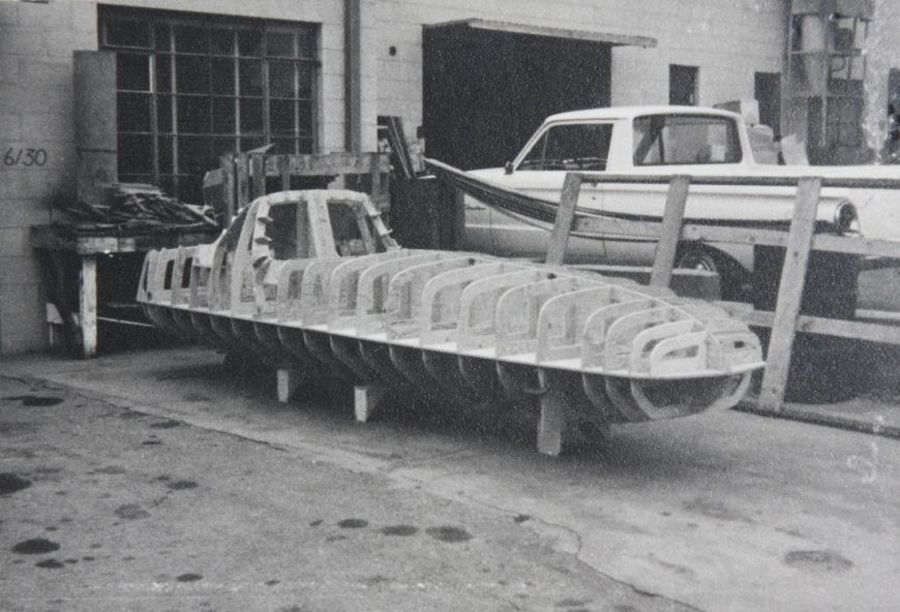

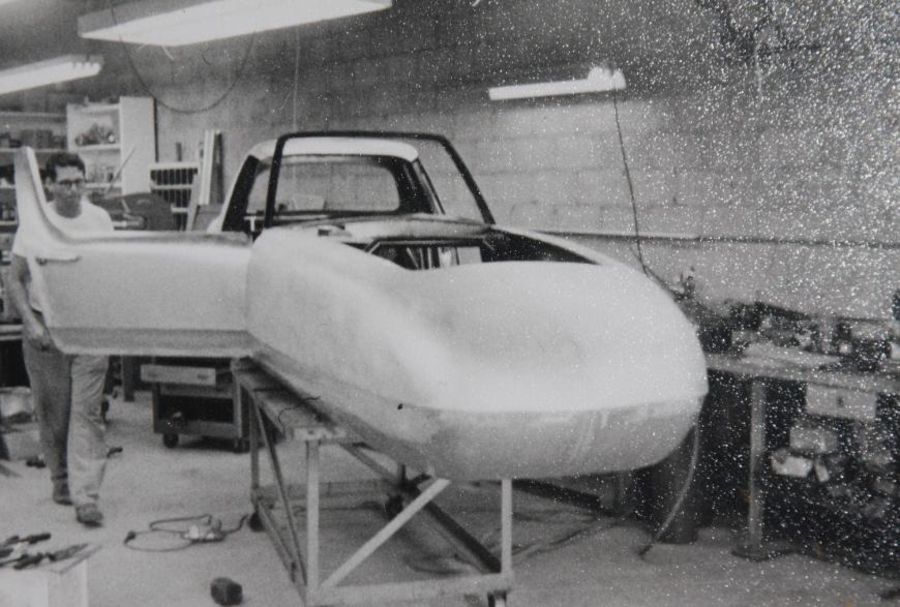

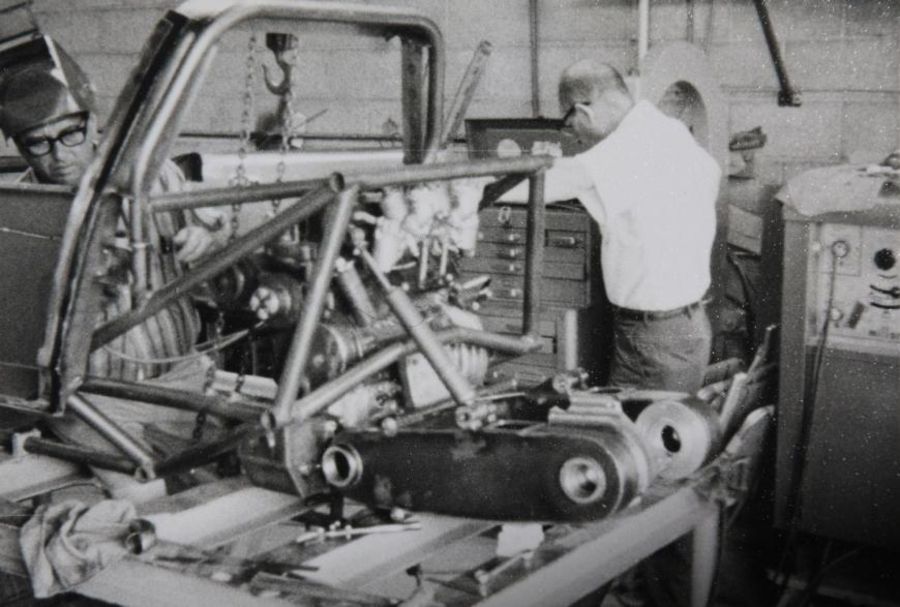

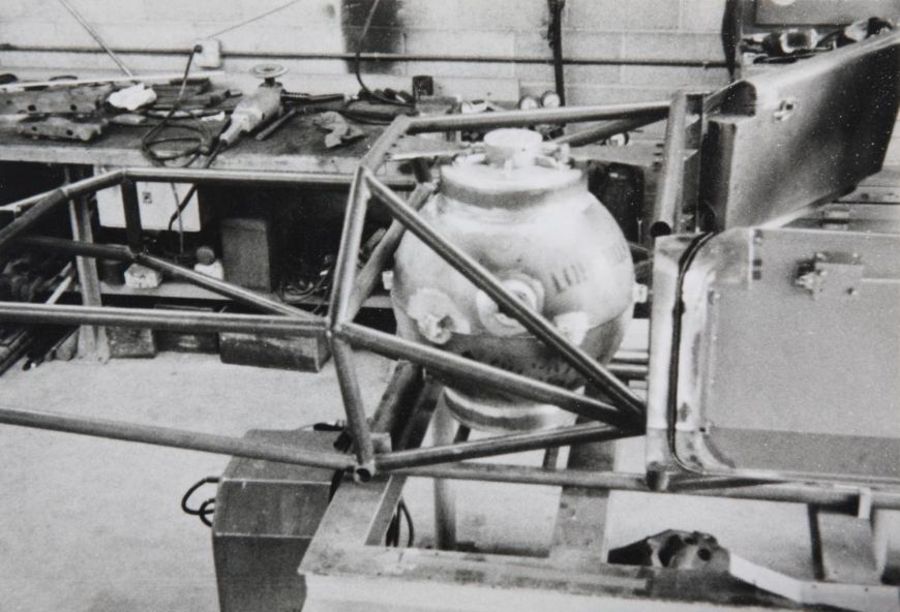

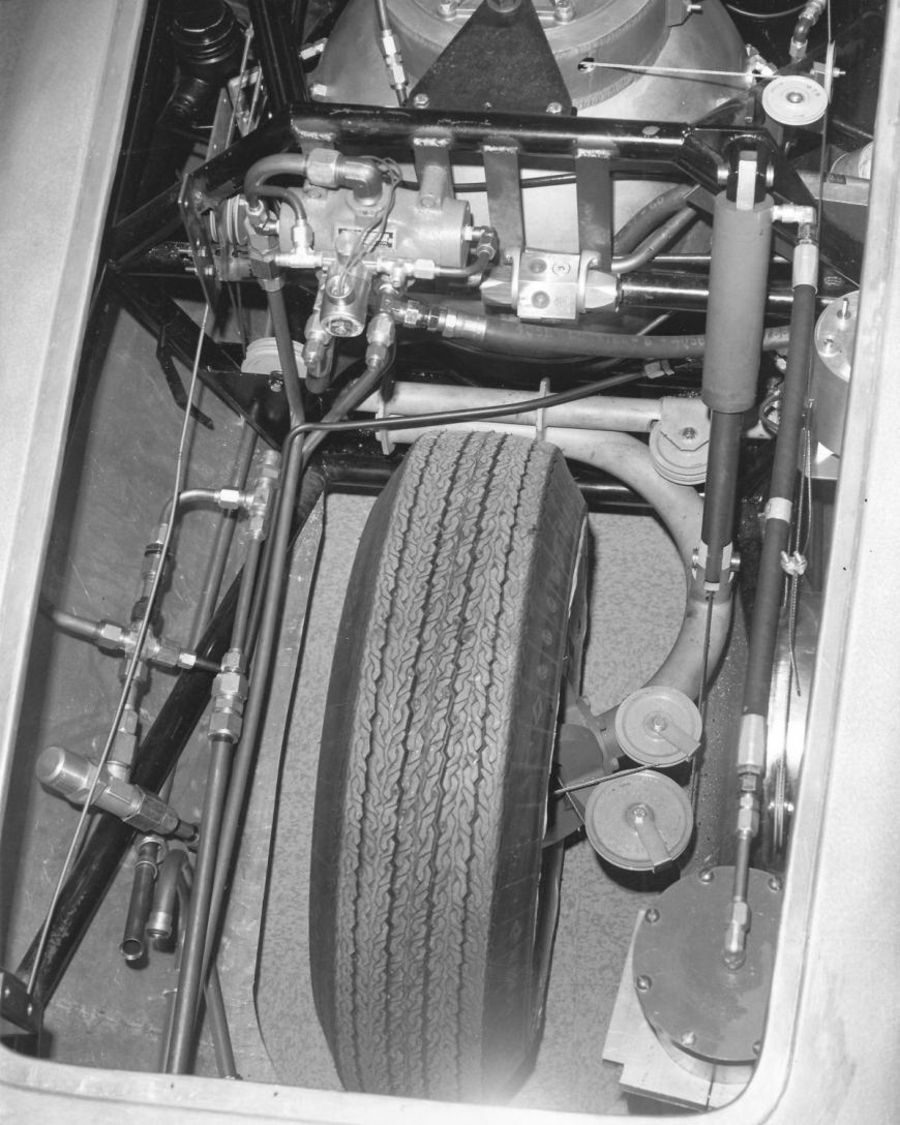

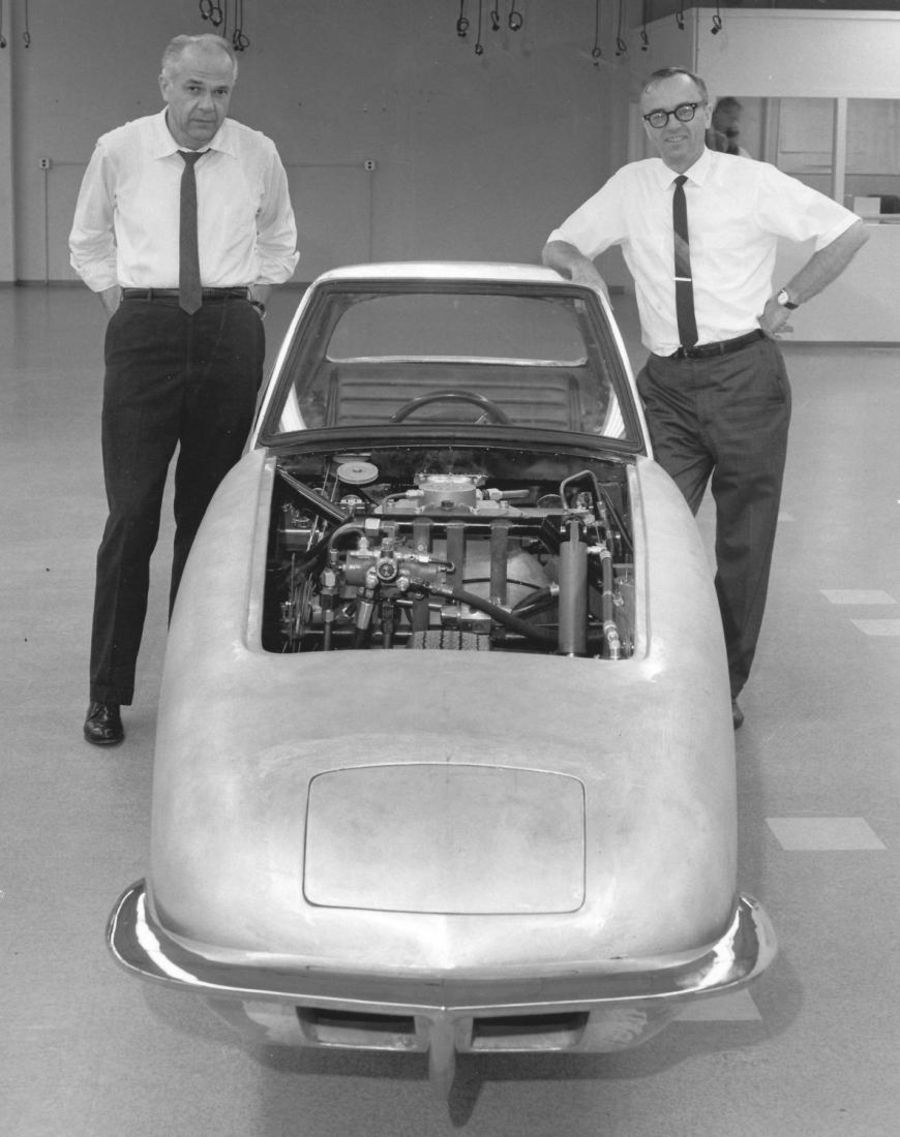

Powered by a 1,275cc four-cylinder from a Mini Cooper, most likely chosen because it was small and powerful, the Gyro-X was a single-seater with a tubular frame and an aluminum body. The rear wheel was driven by a chain. Keeping the vehicle upright, even when idling, was a hydraulically driven gyroscope that spun at 4,000 to 6,000 RPM; this was mounted in front of the driver. The single operational prototype was produced by Gyro Transport Systems Inc. of Northridge, California, founded in 1963 by Tremulis and gyroscope expert Thomas Summers, whose work had primarily been in rockets and missiles.

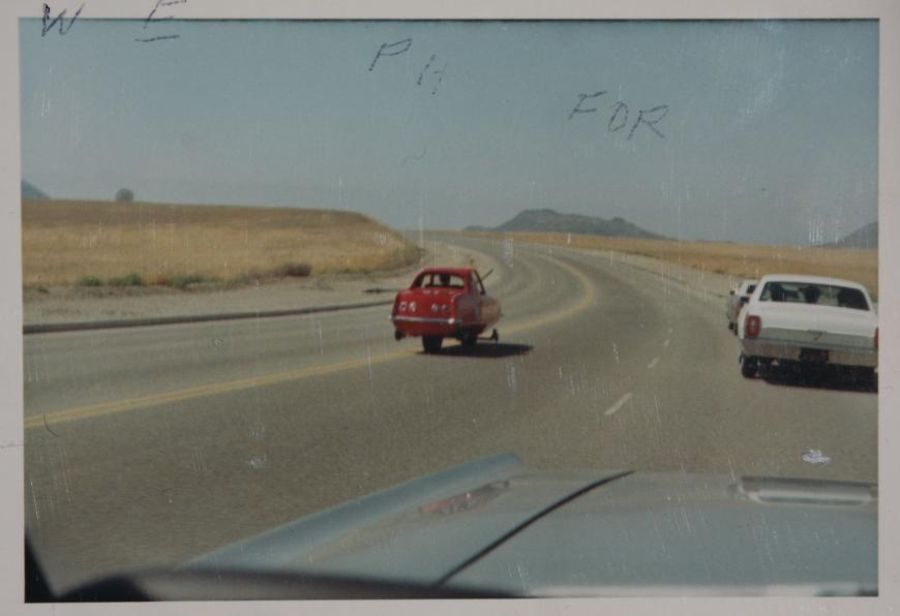

Tremulis believed that the two-wheeled automobile was the cure for traffic congestion; at just 40 inches wide, it would allow the creation of twice as many lanes on existing highways, Jeff says. He was also promising fuel economy of up to 80 miles per gallon. “Alex Tremulis said, ‘Four wheels is two too many,’” Jeff said. “There were a lot of good ideas. Unfortunately, they weren’t able to communicate them.”

The prototype was shown in 1967, attracting limited attention from Road & Track and Sports Cars Illustrated magazines, though Science and Mechanics magazine chose the car for the cover of its September 1967 issue. (There’s some footage of it under way on YouTube.) Why such a gee-whiz vehicle didn’t attract more notice, Jeff doesn’t know, although he theorizes that it might be because the prototype did not emerge until the company was on the brink of bankruptcy.

Assailed by shareholders who wanted their $750,000 investment back, Gyro Transport Systems was out of business by 1970. In 1969, Summers would receive a patent on the car’s gyroscope and hydraulic control system. In the midst of the bankruptcy proceedings, the Gyro-X itself vanished.

About five years ago, it re-emerged, offered for sale by John Needham, a Las Vegas musician who was also known by his stage name, John Windsor. Needham did not know the car’s identity; now minus its gyroscope, the Gyro-X had been converted to a trike, with a mid-mounted flat-four engine and gearbox from a Porsche 914 driving the (now) two rear wheels. Needham had obtained the car around 1994 as collateral for a debt that went unpaid; in 2004, he put up a YouTube video, seeking anyone who knew anything about the car.

The car wound up at the Lane Motor Museum “through luck and good friends,” Jeff said. Collector Mark Brinker of Houston, Texas, heard about the car and bought it. He called Jeff to tell him about his find; “I had never heard of it. No idea,” he said. Mark had intended to restore the car, but changed his mind, and offered it to the Lane Motor Museum, known around the world as the home of the unusual; it has more than 330 cars and motorcycles in its collection, with 150 on display at any given time.

The Lane seems the ideal home for the Gyro-X, which will share display space with such aeronautically inspired vehicles as a propeller-driven car by Marcel Leyat and a Voisin C-28. “Tremulis was always on the go, always thinking of the future, always wanting to try innovative things,” Jeff said. “He’s like [Gabrielle] Voisin, he’s like Leyat – he was always thinking and dreaming.”

No one has any idea what happened to the car’s gyroscope, Jeff said, though speculation is that Summers took it with him when Gyro Transport Systems collapsed. The Lane has hired Thrustcycle Enterprises, a Hawaii company producing gyro-stabilized vehicles, to fabricate a replacement for the Gyro-X’s missing unit. He notes that the condition of the original aluminum skin is undamaged; “This leads us to believe that during testing the car never malfunctioned and never turned over, for if it had the aluminum skin would have to been repaired and it has not been.”

Ever the optimist, Jeff hopes that other pieces of Tremulis’s gyromobiles still exist, unrecognized, and might yet turn up. The original gyroscope, or Tremulis’s engineering drawings for the Gyro-X, or even the gyro-stabilized “pack mule” vehicle built to tempt the interest of the U.S. military might all be in warehouses somewhere, ready to be discovered. (Another Tremulis design, the Gyronaut X-1, a land-speed-record two-wheeler that ran without the gyroscope it was originally intended to have, is also under restoration, documented by Tremulis’s nephew, Steve.)

The Gyro-X will once again move under its own power. Jeff wouldn’t have it any other way. “The point of a car is to see it go and see it work,” he says. “That’s the real magic. It needs to be what it was back in 1967.” And when it is, he’s looking forward to taking a turn behind the wheel. “I’m ready. I am,” he said.