Exactly what niche it fit into, nobody can quite agree, even today. Minivan? Motorhome? Executive limousine? It seemed ahead of its time and outside of time at the same time, and perhaps that’s why only one Kershaw Kruise-Aire was ever built.

Looking something like a cross between a Weinermobile and a GMC Motorhome, the Kruise-Aire emerged from the Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, workshops of Glenn Pray, whose Cord 8/10 can be considered one of the world’s first continuation or replica cars and whose fans are gathering this year to celebrate the car’s 50th anniversary. Yet for all of Pray’s work designing and building the Kruise-Aire, the idea behind the unique vehicle goes to another businessman, Royce Kershaw.

Kershaw, of Montgomery, Alabama, established his company in 1924 to build and service railroad tracks and later to develop machines for track maintenance. The success of his company afforded him the opportunities to take his family on numerous vacations, according to his son, Royce Kershaw Jr., and those vacations led to a keen interest in motorhomes as far back as the late 1940s.

“I remember he took the family to Yellowstone in a new 1949 Ford station wagon when I was eight years old,” Royce Kershaw Jr. said. “And the whole time he was measuring and sketching more for a motorhome-type vehicle than he was vacationing.”

That experience led him to build his own motorhome sometime in the late 1950s, but he appeared dissatisfied with it. Years later, however, two independent purchases led him to revisit the idea and fortify it with aspects of both: a cabin airplane and an Oldsmobile Toronado. According to Royce Kershaw Jr., his father felt the plane’s configuration would work well in an on-the-ground limousine, while the Toronado’s front-wheel-drive platform would keep the passenger compartment low.

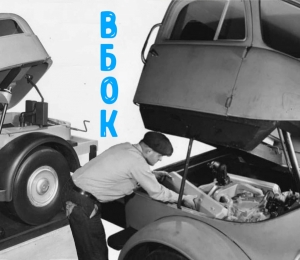

As Josh Malks relates the story in Glenn Pray: The Man Who Brought Legends to Life, which includes these two photos of the completed Kruise-Aire, Kershaw approached a number of Detroit coachbuilders with his idea, all of which turned him down, before he met up with Pray at the 1966 Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Club’s reunion and pitched his idea. Pray agreed, charging $10,000 for the initial designs for the vehicle.

Royce Kershaw Jr. said that his father believed Pray could produce exactly what his father wanted, and that Pray even brought in Gordon Buehrig to participate in the vehicle’s design. Once Royce Kershaw approved of the design, he then sent Pray a 1967 Toronado that he bought new specifically for the drivetrain. “He ordered it with the high-performance 425-cubic-inch V-8 and didn’t want any options on it at all,” Royce Kershaw Jr. said. “Dad always thought everything had to have performance.”

Pray designed the Kruise-Aire to be built from two fiberglass halves that joined together at the beltline “like a walnut shell,” Malks writes. It would sit on a 120-inch wheelbase – just an inch more than the Toronado’s – and use the Toronado’s rear suspension as well as a number of off-the-shelf parts, including a Corvette front bumper, Pontiac headlamp doors, Camaro taillamps, GM pickup windshield, and 1934 Auburn grille screens. Aside from the driver’s door, it had only one entry door for passengers on the curb side. “It was more meant to be chauffeur driven,” Royce Kershaw Jr. said, countering Malks’s assertion that the Kruise-Aire was a sort of proto-minivan.

“It took about a year to build,” Royce Kershaw Jr. said. “We’d fly out there to check on its progress about once a month. Oldsmobile even sent some of its engineers down to consult on the project, and they provided some heavier torsion bars up front. For the interior, we took it to Dean Howard’s aircraft interior shop in San Antonio.”

All told, Malks said that Kershaw spent about $65,000 to build the Kruise-Aire, and Royce Kershaw Jr. said that his father even had plans to go into limited production with it – thus the extensive use of already-available trim items. His father did at least use it a few times – mostly to take his customers to view his equipment in the field – but died about a year after it was complete, leaving it to his son.

Along with his father’s initial attempt at building a motorhome, the Kruise-Aire remains with Royce Kershaw Jr. today.